Here are 7 of the most alien-looking locations right here on Earth.

Etosha Pan, Namibia

When scientists studied images shot by the Cassini space probe of Ontario Lacus, a massive lake on Saturn’s moon Titan, they discovered that it was a depression that drains and refills from below, at low ebb exposing liquid areas ringed by materials such as saturated sand and mudflats. If you get past the fact that it is filled with liquid hydrocarbons, Ontario Lacus bears an eerie resemblance to a place back on Earth — Namibia’s Etosha Salt Pan.

This dried lake bed fills with a shallow layer of fluid from groundwater during the rainy season; the fluid evaporates during the dry season, leaving sediment marks. Etosha, whose name means “great white place” in the language of the Ovambo people, is a 1,800 square-mile (4,800 square-kilometer)expanse of shimmering, dry, baked clay that looks suitably otherworldly.

Atacama Desert, Chile

The Atacama, which stretches 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from Peru's southern border into northern Chile, is what climatologists describe as an absolute desert. It is filled with sterile, bone-dry stretches where rain has never been recorded for as long as humans have been measuring the weather. As a result, much of this parched area is totally devoid of vegetation.

With features such as sand dunes and lava flows, it's not hard to imagine the Atacama as being similar to the landscape that robotic probes — and someday, astronauts — would find on Mars. That's one reason that NASA has used the Chilean desert as a test site. In 2005, for example, a NASA probe detected microbial life in the Atacama's seemingly barren soil, as scientists are hopeful that they'll also be able to do on Mars.

Deep-ocean Thermal Vents, Galapagos Rift, Pacific Ocean

Inside the vents, water heated by volcanic activity sometimes reaches 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius), thanks to the intense pressure from the water above that keeps it from boiling away. That hot water dissolves metals and salts as it moves along rocks, eventually rising and pouring out into the bitter cold, pitch-black darkness.

The vents also spout hydrogen sulfide, a gas which is poisonous to most land-based life. Even so, the vents are home to bacteria, which have evolved to use the seeming poison as an energy source. Scientists think these microbes may closely resemble the earliest life-forms in Earth's oceans.

Rio Tinto, Spain

Spain's Rio Tinto river conjures up images of what a river might look like on some alien world that future astronauts had turned into a mining colony. For thousands of years, generations of miners have dug shafts into the local soil in pursuit of mineral wealth. The Romans fashioned some of their first coins from the Rio Tinto area's gold and silver, and today, the area is one of the most important sources of copper and sulfur on the planet.

Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Idaho

This 618-square-mile (1,600-square-kilometer) region bears an eerie resemblance to the meteor-battered lunar surface. Actually, though, its scarred landscape is the result of the stretching movement of Earth's crust over the past 30 million years. As the crust stretches, it releases pressure on to the hot rocks below, causing them to melt. The hot magma then flows along weaknesses in the surface and results in multiple periods of volcanic activity, the most recent one about 2,000 years ago.

The Pinnacles, Australia

Even if you were an artist painting a cover picture for some pulp science fiction novel, you probably wouldn't envision an alien landscape that looks weirder than The Pinnacles. This stretch of desert landscape in Australia's Nambung National Park boasts thousands of weathered rock projections that rise out of yellow sand dunes — some topped by domes, while others form jagged, sharp-edged columns. The spires, some of which reach 11 feet (3.5 meters) in height, are limestone formations sculpted by wind, vegetation, rain, sun and time over millions of years.

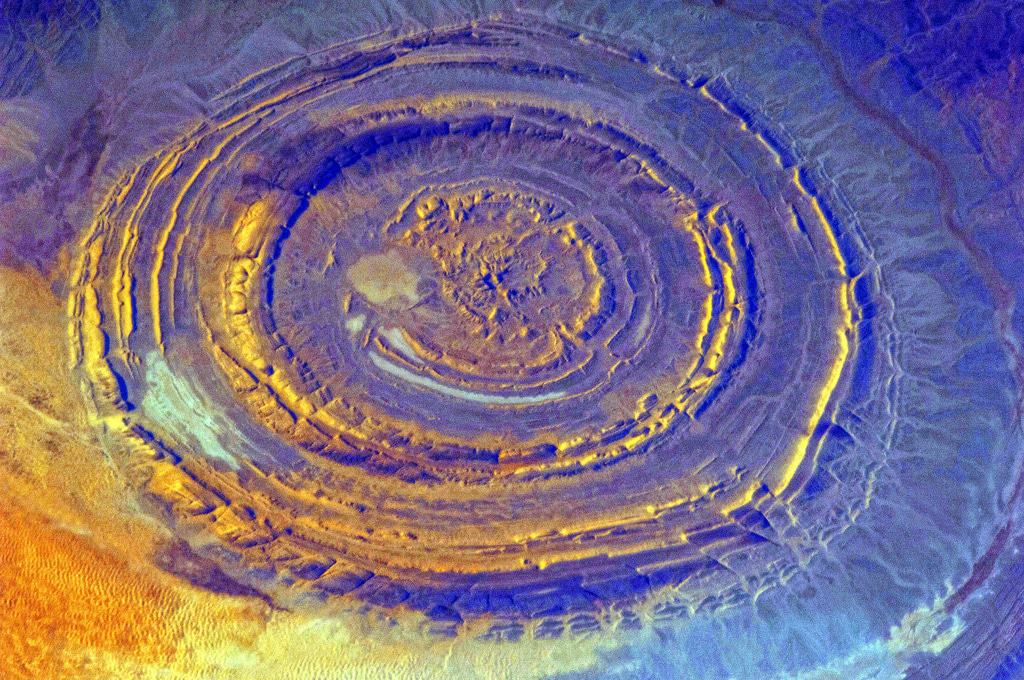

Richat Structure, Mauritania

The Richat Structure in Mauritania is a gigantic circular swirl, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) in diameter, that forms a bull's-eye in an otherwise featureless expanse of west African desert. When astronauts first noticed the Richat Structure in the 1960s, it was believed to be a crater left behind by an immense meteor, because of the uniformity of its curves. But scientists now think that it's a rock formation of Paleozoic quartzites, laid bare by erosion. Either way, though, it's plenty strange looking.