Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Stretching some 1,200 miles along Australia’s Queensland coast, this bio-diverse natural wonder contains the largest existing cover of coral reefs and remains the only living thing that can be seen from space—yet even a landform of this size cannot evade the small yet devastating changes in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Worldwide jumps in carbon dioxide have contributed to the steady deterioration of vulnerable, slow-growing corals—and the Great Barrier has lost half of its coral cover in the last 30 years. Not to mention pollution from industrial port development and outdated fishing practices, which continue to damage the sea floor and its marine residents. UNESCO spared the icon from an “in danger” listing, but warns that significant conservation progress must be made.

The Dead Sea, Israel

Time is running out for this hyper saline lake, the saltiest spot on Earth, and a swimmer’s favorite thanks to its natural buoyancy. A vital resource for the region, the Sea is the sole feeder of the Jordan River as well as a major center for health research. The last four decades, however, have seen irreversible damage, as mineral mining from farmers and cosmetic companies continue to drain the sea of its rich resources.

It’s lost a third of its contents—for proof, look to the former seaside restaurants and hotels, now isolated a mile from shore—and an even greater threat looms: sinkholes, appearing where the water has retreated, bringers of freshwater that dissolve even more salt from the land. Scientists have determined that the coastline recedes by some 3 feet per year, and give it 50 years before it’s gone for good.

Tsukiji Fish Market, Tokyo

The world’s largest fish market is a sight to behold: for generations, throngs of tourists and locals have shuffled through the wholesale arcade of 1,200 stalls, haggling with fishmongers for fresh catches of the day, from swordfish and caviar to seaweed and salmon. Before dawn, even before the crowds descend, live tuna auctions are held—a sight witnessed only by a lucky few each day. Sadly, your chance to see this storied landmark in its original location is officially over, as it moved to Toyosu, across central Tokyo’s Sumida River, in preparation for the 2020 Summer Olympics.

The Congo Basin, Africa

Rain forests produce a large chunk of the world’s supply of oxygen. As they shrink, less carbon dioxide is absorbed, adding to climate change. Research reveals that two million acres are lost every year in the Congo Basin, the world’s second largest rain forest after the Amazon, due to illegal logging, ranching, mining, and civil warfare. And newly paved roads double as easy access routes for poachers to track down endangered species like mountain gorillas, okapis, bonobos, and forest elephants. If conversation efforts do not amplify, scientists estimate that up to two-thirds of the forest might be lost by 2040.

Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa

Whether by human pollution or the Earth’s natural cycle, global warming is real, and it’s been happening longer than we thought. Scientific studies have determined that the snow and ice capping Africa’s highest mountain have been receding by 1% a year since 1912, and that ice stopped accumulating in 2000. Melting ice exposes the mount’s dark-colored soil, which absorbs more heat, causing glaciers to melt faster, and…..you get the picture. Kilimanjaro’s mountaintop ice fields have been an ultimate destination for climbers throughout the years, but, at the current rate of decline, no glaciers are expected to survive in 15 years.

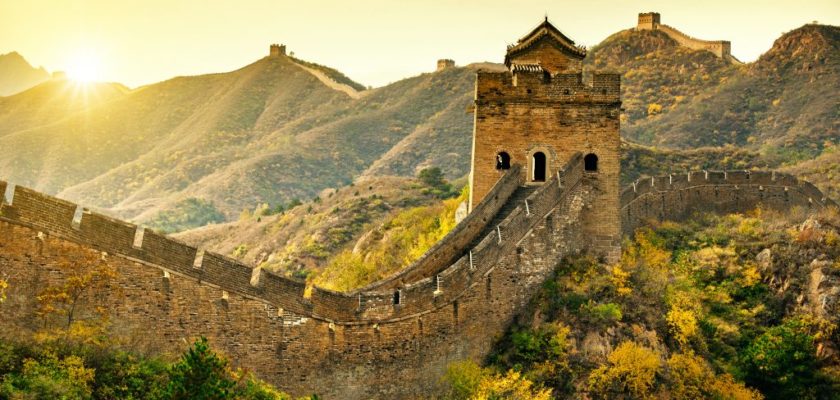

The Great Wall of China

The world’s largest man-made structure, a mighty fortification built to protect a kingdom and a bucket list destination for travelers across the globe, has survived for over 2,000 years, but its legacy may be nearing an end. A third of the wall has been reduced to ruins, eroded from over-farming, looting of bricks, and inevitable old age. The best-preserved section, erected in stages during 14th through 17th centuries under the Ming Dynasty, still stands—but how long before it too gives in to the test of time?

Venice, Italy

The medieval city is postcard-perfect, its intricate network of canals wending through ancient cobbled alleys and under bridges, a window into the Italy of the 5th century. But Venice, built on top of an unstable lagoon, is sinking, and worsening, recurring floods have only sped up the structural damage inflicted on Venice’s low-lying brick buildings and the priceless St. Mark’s Basilica. A mere 3.3-foot rise in sea levels would put the city underwater—a reality that focuses not on “if” but “when.”